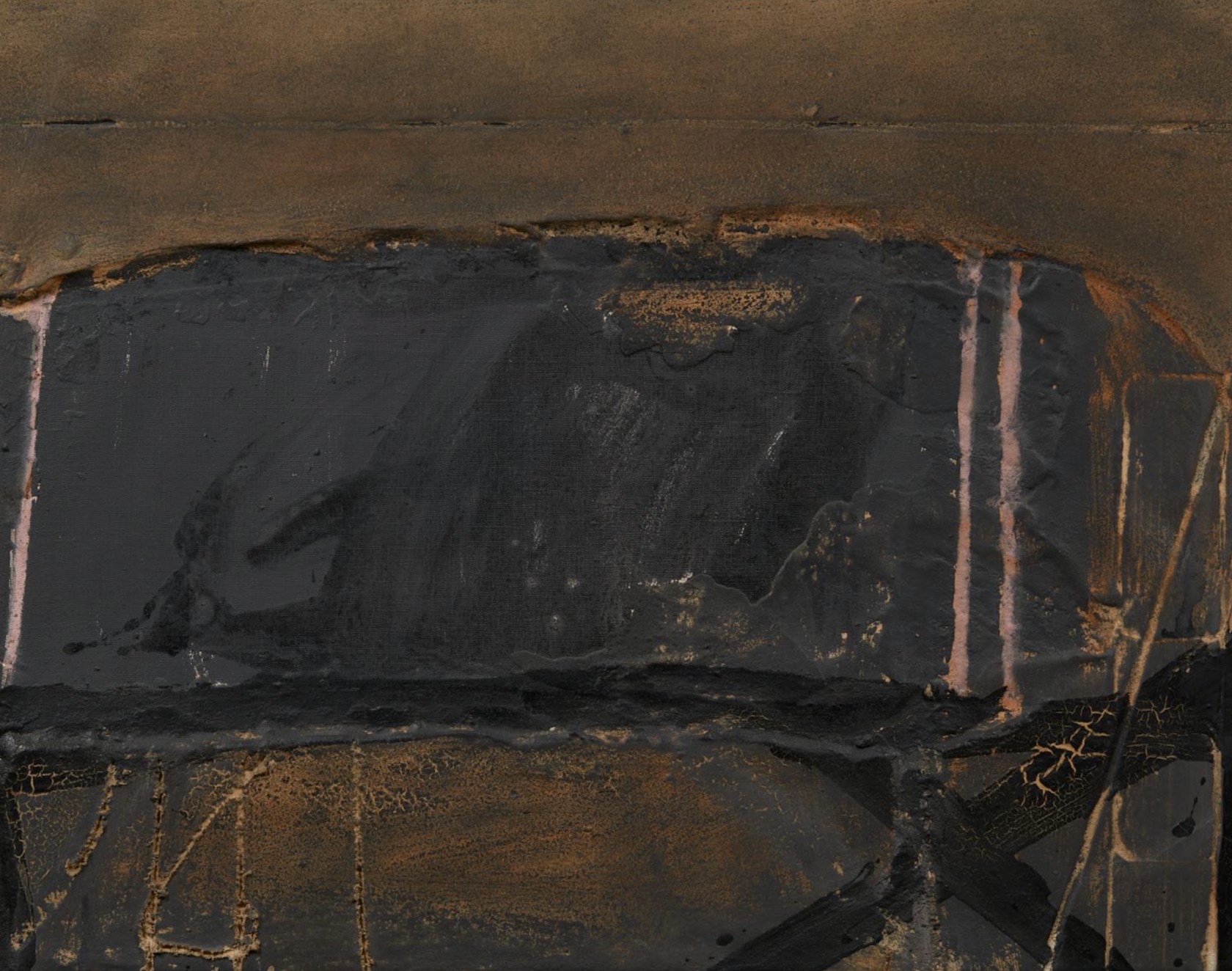

Manolo Millares, detail of Cuadro 96 (Painting 96), 1960. Courtesy of Mayoral.

Black & White: A Visual Language of Oppression and Memory in Postwar Spain

Jordi Mayoral of Mayoral explores the work of visionary artists in mid-20th-century Spain, who were determined to challenge the existing boundaries of censorship

- By Grace Bianciardi

- Meet the Experts

Mid-20th-century Spain was a period of profound political and social upheaval, marked most notably by the oppressive regime of Francisco Franco. In the aftermath of the Spanish Civil War—from 1936 to 1939 and prolonged political upheaval until 1975—the country endured years of isolation, repression, and censorship. However, this oppressive atmosphere fostered a group of emerging visionary artists determined to challenge the existing boundaries of censorship. These artists— including Pablo Picasso (1881– 1973), Salvador Dali (1904–1989), Joan Miró (1893–1983), Antoni Tàpies (1923–2012), Manolo Millares (1926–1972), Eduardo Chillida (1924–2002), and Antonio Saura (1930–1998)—employed their craft to reflect the world around them and challenge it across figurative and allegoric masterpieces. By navigating these turbulent times through painting, these artists took inspiration from the divided political parties and the hues that surrounded them, as fragmented figures and the use of black and white became not just a stylistic choice but a silent language—one of endurance, resistance, and hope. It was a visual code that captured the emotional weight of a country living under a suffocating dictatorship, while simultaneously yearning for change.

At the heart of this visual language was the stark contrast between light and darkness, a metaphor for the dichotomies that defined the era: “Of freedom against oppression, and hope contrasted with despair,” states Jordi Mayoral, Director of Mayoral, the Barcelona-based gallery specialized in postwar and contemporary Spanish art. “For these artists, black and white represented both the harsh reality of their environment and the fragile hope for change that sustained them.” Their works, characterized by the use of textured surfaces, abstract forms, and stark monochromatic palettes, were not merely a matter of aesthetics. “Their palette was a direct commentary deeply informed by the emotional landscape, the trauma of war, political exile, and the need for creative resistance,” Mayoral explains. This monochromatic language and distance from a more figurative approach, served as a new way of explaining the abstract setting that surrounded them.

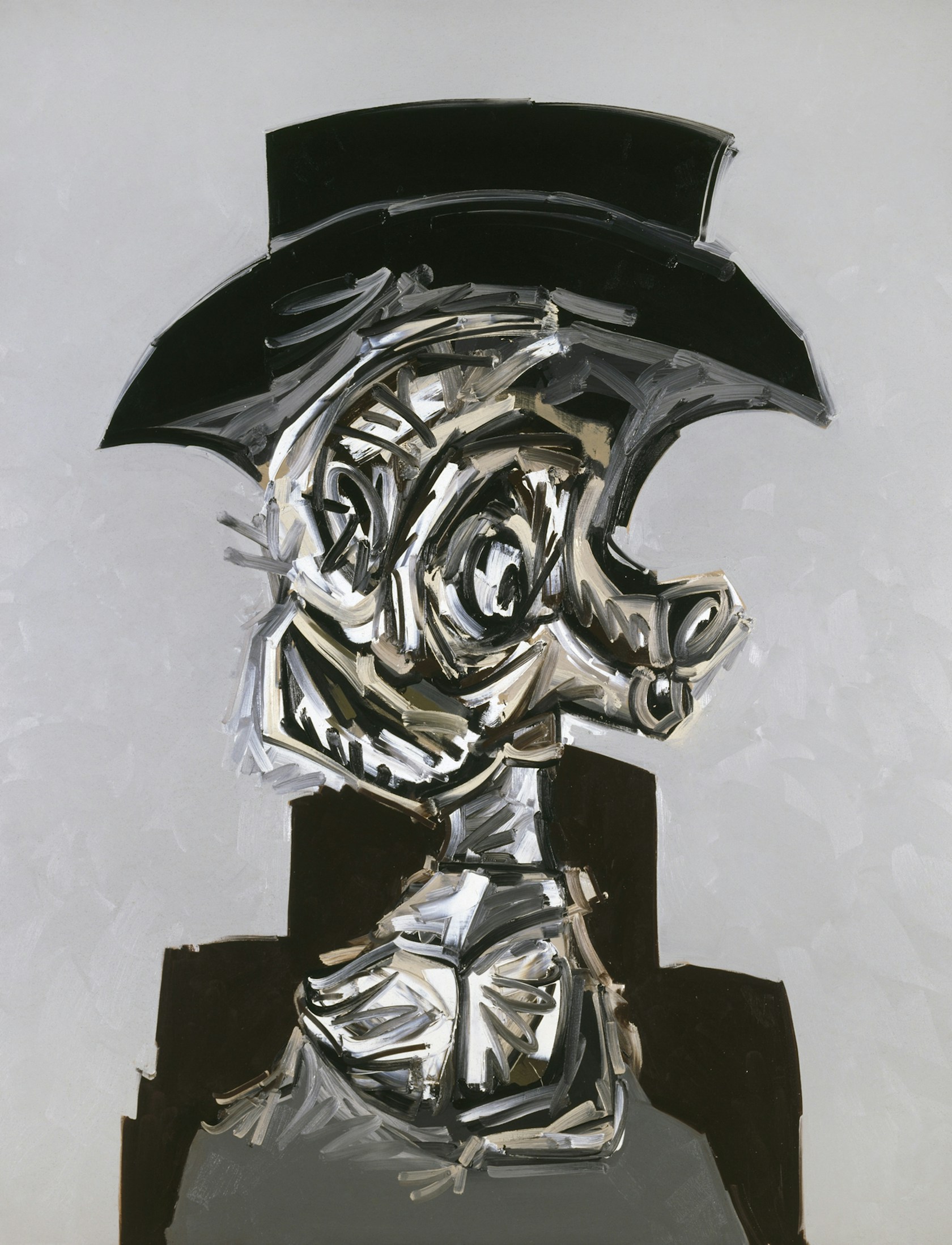

Antonio Saura, H. F. dans son fauteuil (H. F. in his Armchair), 1985. Courtesy of Mayoral. © Succession Antonio Saura / www.antoniosaura.org c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2025.

“When you are creating art, it is because you have hope,” Mayoral shares. “Yet, within the confines of Franco’s Spain, this hope was often muted and reflected in the absence of color of fragmented figures.” This visual tension, highlighted by the absence of color—apart from tones of red—and the overwhelming, dominant use of black and tones of dark brown “encompassed the expression of two extremes,” explains Mayoral, “mirroring the societal landscape, a country torn between the suffocating grip of dictatorship and the long-held desire for democratic freedom.” Picasso’s Guernica (1937) stands as the quintessential example of this visual language of resistance: “Created in response to the devastating bombing of the Basque town of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War, the painting encapsulates the horror of violence and the deep scars left by conflict,” says Mayoral. “Even though it was created before the onset of Franco’s regime, Guernica became emblematic of the oppression and suffering that would follow.” The absence of color in Picasso’s masterpiece and its sharp contrasts between black, white, and gray were not only a reflection of the chaos and destruction of war but also an enduring symbol of the emotional and psychological devastation wrought by totalitarian rule. “When you imagine a dictatorship, you think monochromatically, you do not associate this time with tones of blue, green, and yellow,” Mayoral explains. For this reason black and white became “a visual shorthand for the absence of freedom and for a lack of courage.”

This profound monochromatic use of color was not unique to Picasso. In fact, other Spanish artists active in this period, such as Tàpies, Millares, Chillida, and Saura similarly employed this minimal palette to convey the existential struggle of the Spanish people during the postwar period. In the work of Tàpies and Millares, “the texture and the materials themselves—such as burlap and other rough surfaces—served as metaphors representing the visible, physical, and emotional scars left on the nation,” Mayoral states. “These artists were not creating art for its own sake; they were shaping the collective memory of a society deeply wounded by the surrounding atmosphere of turmoil.”

Antoni Tàpies, detail of Gris Amb Tres Roses (Gray with Three Pink Lines), 1964. Courtesy of Mayoral. © Fundació Antoni Tapies, c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2025.

“Art is a continuous dialogue between generations,” Mayoral states, highlighting the connections between the postwar generation of artists and the impact they had on those that followed them. Contemporary artists such as Juan Uslé and Miguel Berceló are seamless examples of this generational dialogue. “Uslé, like Tàpies employs a combination of abstract techniques, focusing on the tactile quality of the surfaceand the use of color and form to evoke emotional depth,” Mayoral explains. “Barceló’s explorations of texture and abstraction to represent the human condition demonstrate common threads with works by Saura and Millares.”

This sense of continuity was central to the postwar generation’s artistic approach: “These artists sought to create a visual language that not only reflected their own struggles but also resonated with universal themes of freedom, memory, and the fight for a brighter forthcoming time,” Mayoral explains. In many ways, the postwar Spanish artists started speaking a universal creative language. Their works “were painted to impact future history and change the current one,” says Mayoral, and assuch they resonated not only with their Spanish audience but also with artists and collectors across the globe. The monochromatic use of color in their paintings can be seen as part of a broader postwar aesthetic, onethat was “deeply concerned with existential themes and the quest for meaning in what appeared to be a fractured political atmosphere.”

Today, “the legacy of Spanish postwar art is gradually emerging among renowned international institutions and private collections, as the historical significance of these works is becoming recognized,” says Mayoral. “Their relevance extends far beyond Spain because their themes are universal: the struggle for freedom, the memory of the past, and the desire for a better future.” Transcending time and place, the themes of trauma, memory, and resistance that these artists explored resonate today just as powerfully as they did in the postwar era. “Art has a unique ability to speak across generations ,” shares Mayoral. “It is not just a reflection of its time—it shapes the future.” And in this way, Mayoral concludes that “Spanish postwar art, with its unflinching use of black and white, continues to be a beacon of resilience, a testament to the transformative power of art in the face of uncertain times or oppression.”

Antonio Saura, Nule, 1958. Courtesy of Mayoral. © Succession Antonio Saura / www.antoniosaura.org c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2025.