Detail of a work in progress in Jenna Gribbon’s studio. Photo: Vincent Tullo.

For Jenna Gribbon, Paint Always Gets Personal

“Each person is an entire world, and I can explore endlessly,” says artist Jenna Gribbon on painting her favorite subjects: her wife and son

- By Stephanie Sporn

- Meet the Artists

Painter Jenna Gribbon has always had a flair for observation, or as she puts it more bluntly, “a staring problem.” “My wife frequently has to point it out. I just get so absorbed in the ‘looking’ that I forget that I can also be seen. Like Ralph Waldo Emerson [wrote], ‘I become a transparent eyeball; I am nothing; I see all.’” While the Brooklyn-based artist, born in Knoxville, Tennessee, has been painting her entire life, over the last decade she has honed her signature style and subject—theatrically lit portraits of her partner, Mackenzie Scott (the musician TORRES), engaging in quotidian, tender, and occasionally defiant acts. With her candid depictions, at once raw and fantastical, vulnerable and unflinching, Gribbon has cemented herself as one of today’s most captivating figurative artists, inviting the viewer to be a “transparent eyeball” in her intimate world.

While Gribbon is known for her portrayals of sapphic desire, the artist cautions against labeling her work as “hyper-romantic or hyper-sexual.” “People are very quick to equate nudity with sex. It’s actually a small percentage of the work that deals directly with eroticism or sex,” she says, adding that romantic under- or overtones are an inevitable “byproduct” of her relationship to her partner, rather than “the goal.” “I’m always just trying to show the experience of seeing and re-seeing a person who’s so close to me, and to show how much of an undertaking it is to do that in earnest.”

Jenna Gribbon in her New York studio. Photo: Vincent Tullo.

While Gribbon has been painting her now teenage son his whole life, in recent years he has become a more prominent subject, especially in how he has come to resemble Gribbon and consequently complicate her understanding of herself. The resulting portraits read like close character studies, where seemingly fleeting moments, reflecting varying degrees of being staged versus spontaneous, are made permanent on canvas. Gribbon’s process is a collaborative one in which she speaks with the subject about her goal for that specific painting. “We have conversations about the role they’re playing and how they feel comfortable being perceived,” explains the artist. “They often participate in how [the painting is] produced, holding a light for example, and I’ll regularly include parts of my own body to acknowledge my own presence in relation to my subject.

Gribbon’s experimental renderings, all captured in thick Impressionistic brushstrokes, are heavily rooted in her love of film. The artist’s chief sources of cinematic inspiration range “from the verité examinations of self and subject of Agnès Varda to the utterly elegant magic of Jean Cocteau and the theatricality and strange opulence of Rainer Werner Fassbinder,” a leading filmmaker in the New German Cinema movement. Gribbon likens her “strategy of revealing lights, green screens, etc. to show the seams of production” to Dogme 95. A mid-’90s Danish movement, Dogme 95 urged filmmakers to tell stories through more simplistic, authentic methods, such as only shooting on location and using hand-held cameras, in contrast to the industry’s increasing reliance on high-budget, high-tech production.

Gribbon’s studio, featuring a painting of Gribbon’s son. The artist paints her wife and son in various scenarios, ranging from the intimate to the highly theatrical and staged. Photo: Vincent Tullo.

Gribbon employs a similarly measured approach in her paintings’ palette and ambience. “If I try to deviate too far from the reality of the color of the light, the spell is broken, and the magic of the illusion is lost,” she says. However, “there’s lots of room to play with localized color of the objects or figures themselves, and I pump up the chroma and/or mute it wherever I can in service of the mood of the painting.” Her subjects’ neon nipples, for example, “operate under their own logic.” “They’re anachronistic and prevent the figure from feeling like a historicized nude,” she explains. “They have a powerful, almost sci-fi effect, as if maybe they’re their own light source.”

Nevertheless, Gribbon’s cognizance of art history, whether it’s tropes or visionary figures, is often reflected in her work. The artist has long admired Édouard Manet’s and Mary Cassatt’s paint application. As a child, she “pored over the pages of a book on Mary Cassatt paintings” and was especially “obsessed with the brushstrokes.” Frequently depicting women and children, further parallels can be drawn between the American Impressionist’s intimate interior scenes and Gribbon. As for contemporary artists, Gribbon praises Karen Kilimnik for her “intriguing combination of approaches,” a decided mix of “sweetness, irreverence, and coolness.”

Some of Gribbon’s materials in her studio. Photo: Vincent Tullo.

Gribbon paints alla prima, an italian term meaning “at first attempt,” in which paint is applied wet into wet, yielding bold and fresh paintings that capture fleeting moments. Photo: Vincent Tullo.

In terms of key influences, Gribbon underscores Varda’s significance, not just for her New Wave films but also as a photographer and artist who “intentionally oriented the viewer to what she’s making by bringing herself into the work.” Interrogating the subject-artist-viewer relationship is essential to the evolution of Gribbon’s increasingly self-referential œuvre. Early in her career, the artist primarily painted empty New York apartments, which she would then insert people and objects into so that they wouldn’t reflect light or cast shadows. “It was about superimposing myself and my world into alien spaces and making a home of them,” she explains. Nowadays, if Gribbon’s likeness isn’t conspicuously featured, her hand or leg often make a Joan Semmel-like appearance, as if extending out directly from behind the canvas. “Somewhere along the way, I became a more embodied person … 20 years ago I would’ve been embarrassed to let the paint feel so personal,” says Gribbon, acknowledging that by abandoning her fears of seeming narcissistic, the paintings became “a lot more fun.” The response has been overwhelmingly positive: “People can feel the enjoyment in the paint.”

Inside Gribbon’s New York studio. Photo: Vincent Tullo.

Another turning point came in 2017, when Gribbon met Scott. Whereas the artist had previously painted numerous friends and loved ones, her practice shifted to focusing almost exclusively on her partner. Paradoxically, limiting her subject matter proved far from a challenge. “The process of finding new ways to approach her or my son is very tied to the process of seeing them with new eyes on a daily basis,” says Gribbon. “Each person is an entire world, and I can explore endlessly. There are infinite paintings a day I could make of each of them—just the turn of a head is a different painting.”

As she’s grown into her painterly predilections, Gribbon has come to welcome spontaneity. On what her ideal painting session looks like, she says, “I have a whole open day in front of me with no diversions, and I’m able to let go of some of the control and let the painting happen without overmanaging it. Ideally something happens with the paint that’s surprising and better than I could have planned.” Having described her childhood as being “defined by [her] pursuit of escapism,” it’s as if Gribbon has found the ultimate escape in fully succumbing to her artistic process. Consequently, she becomes as lost in the moment as her subject appears to be, making the resulting image feel like a snapshot from the artist’s own memory.

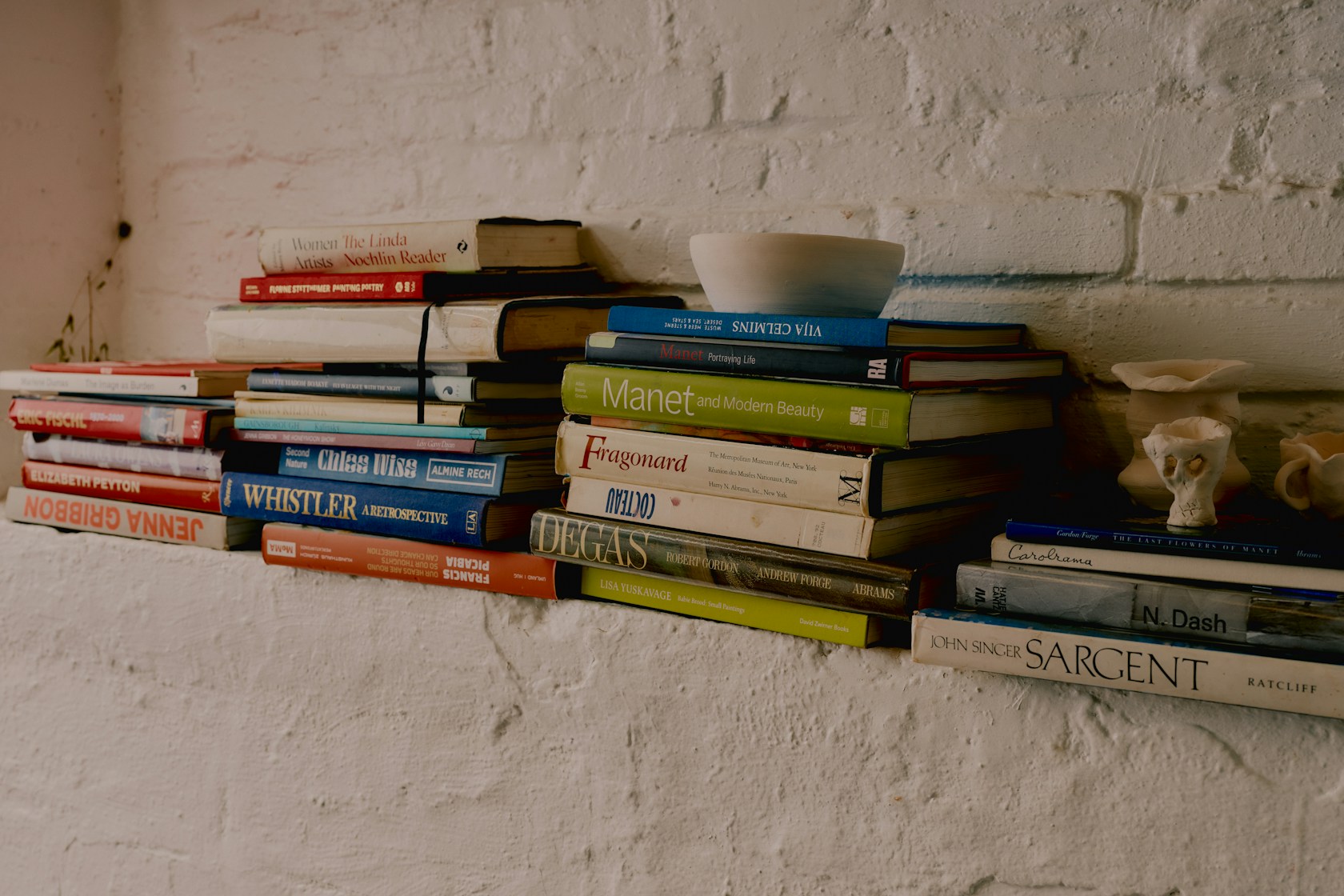

A selection of Gribbon’s books, reflecting a range of art-historical references. Different books rotate in and out of the studio depending on what the artist is working on. Photo: Vincent Tullo.

Looking ahead, Gribbon will have a solo show at MASSIMODECARLO in Milan this summer, as well as a major survey of her work at the Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University in Massachusetts in 2026. As for long-term goals, the artist wishes for her deep connection to her work to never fade. “I need to feel like I’m always discovering something,” she says. Luckily for Gribbon, equipped with a keen eye and eternal admiration for those closest to her, discovery is just a gesture away.

Jenna Gribbon is represented by TEFAF exhibitor MASSIMODECARLO.